|

|

The Arch of Metahistory:

Sacred Nature

Whatever the origins of humanity in cosmic

terms, its immediate source is Nature, the habitat provided by

Gaia, the living planet. All preliterate traditions around the

world reflect the belief that the natural world is charged with

magical and spiritual power variously called mana, wakonda, dema,

deva and many other names. All of these words indicate the

presence of the sacred in the realm of the senses, not in some

remote realm beyond human reach. Almost universally, this presence was imagined in the form of a Goddess, not a God.

In the beginning there was Isis-Hathor:

Oldest of the Old. She was the Goddess from whom all Becoming

arose. She was the Great Lady, Mistress of the Two Lands of

Egypt, Mistress of Shelter, Mistress of Heaven, Mistress of the

House of Life, Mistress of the Divine Word. She was the Unique.

In all Her great and wonderful works She was a wiser magician

and more excellent than any God.

-

Theban sacred text,

14C BCE, Egypt.

Sacred comes from the Sanskrit root sak-,

“to be powerful”. What supports something must be more

powerful than that which it supports. Thus, Nature, which

supports life, is more powerful than humanity, which is but one

species woven into the web of Nature. Whether God creates Nature

or Nature itself is God, the mysterious wellspring of life is

sacred and all forms of life partake of that sacredness.

The certainty that Nature is sacred is the

point of departure for all forms of human spirituality, and so

it represents the founding stone of the arch of metahistory. If

the arch is imagined as a bridge, Sacred Nature is the footing

that has to be erected on the bank of the river from which we

proceed. Life proceeds from Nature and all human activity is

grounded in the Gaian habitat. All stories and scripts that

encode beliefs about our relation to Nature reflect this master

theme.

In the religious life of humanity, God first

appears in Nature. Only later does God depart and hover outside

as the disembodied creator of the natural world. Religion

originates in “nature-worship” The Divine thus recognized

is invariably feminine: hence, Gaia is a goddess, not a god.

Long before institutionalized religions arose, the Nature

Goddess was the Supreme Being. Among the Gnostics she was

understood as Sophia, the Godhead of Nature. Sophia means

“wisdom,” stressing the universal awareness that Nature is

alive and intelligent, wise in her ways. Gaia-Sophia,

all-knowing Mother Nature, appears in many guises in diverse

myths and legends. Sacred Nature and the Goddess are thus

identical. Indigenous cultures constantly assert that everything

they know about how to live comes from direct communication with

the Goddess. These scripts say: Goddess births all, Goddess

sustains all, Goddess knows all.

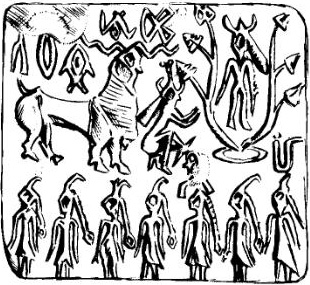

“Animism” is

the name given by anthropologists to the experience (or, if

you will, the belief) that all nature

is alive, animated and

animating. The Goddess equated with Sacred Nature was

embodied in a myriad forms and worshipped in her

manifest guises, such as

trees. (Clay impression, Indus Valley, c. 2000 BC)

Navigator for Psychonautics

All races are born from a single genetic

matrix in Sacred Nature. The Biblical Eve has thousands of

counterparts in other cultures, each one a legitimate version of

the Great Mother. This mythological notion has recently emerged

in scientific theory which now speaks of “Mitochondrial

Eve,” the genetic mother of the entire human species. She is

the biological matrix of the DNA code for all of humanity.

Ancient racial scripts such as the Dynastic history of the

Egyptians confer identity on the people by descent from the

primordial Mother-Goddess known under various names: Nut, Mut,

Neith, Hathor, Isis. In Egyptian religion the continuity of the

blood-lines of the royal family (pharaohs) was constantly

renewed by the Goddess Hathor. The script that asserts that the

Goddess confers authority upon those who will guide society is

one of the most ancient formulas of civilization. Theocracy is

routinely defined by historians as “rulership of human society

by the gods or their descendents,” but this definition is

misleading because it overlooks the central role of the Goddess

in the selection and empowerment of the king who will rule over

civilization. A tremendously problematic issue in metahistory,

sacred kingship links Sacred Nature to Origins in a crucial way.

Many scripts trace the ancestral origins of a

race to the mating of a goddess and a human progenitor, a hero.

Hence, the Trojan hero Aeneas is the son of another hero,

Anchises, who mated with the goddess Aphrodite. Technically,

divine-human intercourse is called theogamy: god-mating.

Stories of theogamy precede stories of theocracy, upon which all

ancient civilized nations were originally founded. The mytheme

of theogamy is prevalent in many indigenous cultures and it was

widely evident in pagan religion, but the subject matter

associated with this motif (including the controversial

practices of temple prostitution and sacred sexuality) came to

be diabolized and forbidden when the Judeo-Christian ethic rose

to dominance.

The Trojan War dates to 1200 BC, but more

than 2000 years later charters written for the royal families of

Europe cited Aeneas as their racial-national ancestor. To this

day, many families of the European nobility still trace their

ancestral lines back to mythological figures. In Japan the

Emperor was viewed as the “Son of Heaven,” a human being of

divine ancestry, until the last Emperor, Hirohito, was forced to

renounce this claim at the end of World War Two. Among

indigenous peoples, the various tribes and nations are all

children of the Great Mother. The ancient Celts considered

themselves to be the Tuatha de Danaan, “Children of Dana,”

the primordial Mother Goddess who gave her name to the River

Danube.

The scripts say: The Mother Goddess produces

heroes and heroes found races, so she is the common mother of

all races.

When racial-national scripts become

explicitly sexual, the male national heroes, or “founding

fathers,” become more important than the Goddess who mothers

them. Though the role of the Sacred Nature Goddess may be

minimized, the Goddess is always present in the background. In

indigenous societies tribal identity is based on matrilineal

descent, often in the form of identification with magical

totemic ancestors (plants, animals, i.e., sacred forces in

nature). These ancestral bonds are rigorously preserved over the

millennia. The vast spectrum of tribal groups around the world

all share a universal reverence for other species in nature and

recognize spiritual powers in animals such as the lion, eagle,

bear or jaguar. The interspecies bond was profoundly ruptured in

Judaeo-Christian religion that makes humanity superior to all

other creatures. The story of human-species dominance is told in

Genesis where the creator god, Jehovah, gives his progeny Adam

dominion over all the creatures of the earth.

This shift produced what scholars call the

desacralization of nature. The script says: humanity appears

in the natural world but is superior to it. The vital bond

between humanity and Sacred Nature is replaced by a devotional

bond between humanity and the Creator God, outside and above

nature. In the course of human history, the master theme of

Sacred Nature has undergone a massive shift from participation

in nature to domination of it. The consequences of this

monumental shift emerge under the second master theme, Eternal

Conflict.

Due to a seemingly innate antagonism between

the sexes (which no single myth explains) scripts often mingle

these two master themes. In the Bible Eve is the troublemaker

who causes both Adam and Eve to get thrown out of Eden, i.e.,

alienated from Sacred Nature. This script is rather twisty

because it makes Woman, the embodiment of Nature, the cause of a

rupture from the natural world. In the Gnostic version of the

Fall, the twisty serpent who tempts Eve to acquire forbidden

knowledge is presented as a benefactor rather than an evil

interloper. The Gnostic version of the Fall is a rare example of

a direct and deliberate inversion of a script. (Basic Reading:

The

Gnostic Gospels.)

Most scripts on the theme of Sacred Nature

give superiority to the feminine, but some religious texts were

composed with the intent to eliminate the feminine component

from Divinity. The Hebrew Goddess Hokmah, identical with many

pagan Goddesses such as Astarte, Asteroth and Elath, was

originally the wife and co-equal of Jehovah. By the time most of

the Torah (Old Testament) texts were written, a few hundred

years BCE, Her role in the religious life of the ancient Hebrews

was virtually obliterated. The purpose of this script change was

to endorse patriarchal authority and promote monotheism.

Scholars have labored arduously to understand the actual role

played by pagan goddesses in ancient Hebrew culture. (This

effort has been named “Goddess reclamation”)

Within Goddess-based religion, a vast

spectrum of divinities, male and female, comprise the sacred

dimension of the natural world. Imposition of monotheistic

belief went hand in hand with the repression of the Goddess.

Over a period of hundreds of years, the gradual waning of

awareness and belief in the power of Sacred Nature (desacralization)

prepared the way for monotheistic belief in a remote omnipotent

deity.

Religious beliefs converge with familial

scripting when Mother Earth is described as the parent of all

living creatures, all species. This view of the earth implies an

innate human ability to feel reverence toward the natural

habitat — a sentiment partially recovered in the environmental

movement. Except in the case of native-mind cultures, reverence

for the earth as mother has been largely diverted to the human

realm. (The term “native-mind” denotes the outlook of

indigenous peoples who see their values reflected in the habitat

of which they are natives. It is interchangeable with

indigenous.) In many families the mother is still a matriarch

and held to be the mysterious source of life that sustains the

whole family, even though her role and influence may be

crippling to the psychological growth of individual family

members. Likewise, the bond to Sacred Nature can become

pathological and degenerate into blind superstition and sinister

games of power. Taboos around incest and menstruation indicate

how humanity can slip out of harmony with nature into fearful

obsessions.

Incest belongs to the mytheme of

Sacred Nature because it represents the risk of binding the

human family to the Mother Goddess in an unhealthy and

regressive way. Concern about incest is present in most ancient

and tribal mythologies, with taboos to prevent it from becoming

too overwhelming. In the ancient cult of Cybele priests

castrated themselves in honor of the Goddess. This practice

recalls a religious-sexual-familial pattern of great interest in

modern psychology which is full of case studies of men who are

emotionally castrated. The parallel is odd because it appears

the modern male is castrated due to lack of a vital connection

with Sacred Nature, while in the ancient cult castration was

symbolic of dedication to its feminine embodiment, the Goddess.

The mythemes carried in any script or ritualized form of

behavior can mutate, and their meanings can be reversed.

Catholic priests, who renounce sex, are

symbolically imitating the devotees of Cybele, but they do it in

dedication to a male father god, not a goddess. The motif of

castration is constant even though its application varies as the

script varies.

Religious-familial stories that follow the

patriarchal model represent the father as the supreme deity of

the family, a harsh judge who rewards his children only when

they follow his rules, and punishes them severely when they don’t.

The religious script, “God gives commands,”

translates readily into the familial script, “father

knows best” Since father as male deity represents an authority

beyond Nature, this story conflicts with the one that says,

“mother” (nature) nurtures all.

In indigenous societies, the family remains

closely related to Nature as the source of survival. This

dependence generates a set of scripts in which the familial

interactive patterns do not consume the family members, or

obscure each member’s primordial bond with the natural world.

The identity of the family group and the individuals within it

are both reflected in active rapport with Nature — in

participation,

to cite the key anthropological term for this relationship. In

modern life a family dedicated to conservation and exploration

of nature would be acting to restore the primordial bond. Such a

family would operate from scripts that say “nature provides

inspiration” and “nature unites humanity.”

Blackfoot Physics by F.

David Peat compares indigenous views about Nature to the ideals and

assumptions of modern science.

Inanna, by Diana Wolkstein and Samuel

Noah Kramer recovers in vivid erotic language the mystique of

the Goddess central to all pagan and indigenous societies.

Voices of the First

Day by Robert Lawlor presents a deep and far-reaching

evaluation of the worldview of Australian Aborigines, heirs to a

40,000-year-old cultural tradition in which all aspects of

spiritual and practical experience are based on symbiosis with

Sacred Nature. |

|

|