|

|

|

"Seven Classics"

Background Reading for Metahistory

(since 1900)

The Metahistory site contains three sections

with reviews of books recommended for reading and research:

Basic Reading,

consisting of 16 books chosen for their value in general orientation

to Metahistory.

The Arch of Metahistory introduces

the five primary themes of our discourse: Sacred Nature, Eternal

Conflict, Origins, Moral Design, Technology. For each theme,

three books are recommended and briefly reviewed, making a total

of 15 books.

Additional to these 31 books are the "Seven

Classics" suggested for reading relative to the origins

and precedents of metahistory. Reviews of the Classics are longer

than those found in the other sections, because the commentaries

on these books are meant to amplify and extend points raised

in the long essay, Background to Metahistory.

The classics are listed in order of date of

publication. As with all books cited in Metahistory.org, specifics

on publisher, year and edition cited are given in the Bibliography.

The

Golden Bough by Sir James Frazer: 1900

Developed from a series of articles begun in 1885, originally published

in two volumes in 1890, and expanded to twelve volumes by 1900, The

Golden Bough is best known through the two-volume abridgement of

1922. It stands as a literary masterpiece as well as "the fountainhead" of

many, many subsequent inventories and studies. (Doty, 169)

Harking back to Herotodus, Frazer begins with a treatment of the Heroic

Quest figured in Aeneas, the Trojan warrior celebrated as the founder

of Latium (prehistoric Rome). His opening description of the secret

grove dedicated to the Goddess Diana is so captivating that it has

hooked many a reader for the remaining 827 pages. The sacred grove

of Nemi in Tuscany stands by a lake haunted by water nymphs who test

the hero and initiate him into precious secrets. In the classical version

recorded by the Roman poet, Vergil [70 BCE — 19 CE], the Quest

involves plucking the "Golden Bough" (thought to be mistletoe)

and takes Aeneas on the perilous journey into the Underworld to commune

with ancestral spirits.

In the main segue that distinguishes his work, Frazer relates the universal

theme of the Heroic Quest to the drama of the sacrificed king, the

cental figure in theocracy. In alignment that anticipates later feminist

writing (e.g., Merlin Stone, below), he shows how the "King of

the Wood" gains or loses his authority through his connection

with the Goddess Diana (Greek Artemis). In some way the regal candidate

must satisfy the Goddess to be chosen as ruler, and he must periodically

renew his vows toward her to retain his power. In a series of brilliant,

enchantingly written passages, Frazer weaves the drama of sacred kingship

into the larger fabric of universal myth concerning the fate of dying

and resurrecting gods: Adonis, Attis, Osiris, and others.

Frazer’s metahistorical overview was extremely influential in

literature and art in his time, and afterwards. One late variant of

the dying-and-resurrecting god was the "Wounded Fisher King" of

the Grail Legend, popular fare in the Middle Ages. He appears as a

haunting presence in T. S. Eliot’s long poem, The Waste Land,

signature text of the Modernist movement (1885 — 1925). Many other

writers and painters of the era took up Frazer’s motifs. The link

between modern sensibility (especially the tragic sense of having lost

touch with the Sacred) and the timeless mythological themes delineated

by Frazer was further explored in From Ritual to Romance by

Jessie L. Weston. This book became the skeleton key to many artistic

and cultural developments in the period between the two world wars.

Frazer’s treatment of these momentous themes is all the more compelling

now that we have a fuller understanding of how the themes were historically

scripted and enacted. After 4500 BCE a caste of shaman-priests set

up the institution of kingship as a way to extend their power into

the urban centers then burgeoning across Asia, the Middle East and

Egypt. The introduction of agriculture on a large scale had effectively

deprived the shamans of their role as mediators between nature and

society. Once grain was collected and stored in temple granaries, the

crucial role of the shaman in regulating the weather was deeply undermined.

Upon the demise of magic came the rise of political authority, yet

the king remained invested with shamanic and heroic traits long after

his precedents were phased out of the social order.

In the long opening phase of social organization, the hero-king must

be initiated by the Goddess before he assumes the status of the enthroned

theocrat, the ultimate male authority figure. Eventually the Goddess

herself is also phased out. Frazer was not able to trace and articulate

all the nuances of this millennial development, but reading him today

with what we now know in mind, we can fill in the gaps and enrich his

original contribution.

Frazer is still centrally important to metahistory: what he misses

reveals what we have learned.

Sacred kingship is one of the five paramount themes in world mythology.

Another is shamanic magic (now understood to be the hidden force behind

regal male authority, as just explained), to which Frazer devotes the

opening 100 pages of his opus. Frazer introduces us to a staggering

array of motifs: tree-worship, sacred marriage, taboos associated with

sacred kingship, the sacrifice of the king, midsummer rites, particulars

of the "vegetation gods" such as Adonis, Attis, Osiris, and

Dionysos, the myth of Demeter and Persephone (central to the Eleusinian

Mysteries celebrated near Athens), the Corn Mother and other ancestral

spirits, rites of eating the Gods, propitiation of wild animals, exorcism,

scapegoats, Scandinavian redemptive deities such as Odin and Balder,

and European fire-festivals. He concludes with some thoughts on the

conception of the human soul in folklore.

Reading Frazer is a process of slow and deep enrichment and it is almost

always entertaining. I would propose a good six months to ingest The

Golden Bough. It reads best when read effortlessly and at leisure.

Myths to Live By by

Joseph Campbell: 1958 - 1971

At mid-century Joseph Campbell [1904 — 1987] emerged as the foremost

exponent of comparative mythology and the history of religions. He

taught at Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, New York, for almost

40 years. His work comprises a vast sweep of materials brought together

in the four-volume masterpiece, The Masks of God. At the end

of his life Campbell became something of a cult guru in the U.S.. He

was known for being the advisor to George Lucas on Star Wars,

for which Campbell proposed the theme of the battle between Good and

Evil, represented in Persian myth by Ormazd and Ahriman (aka Darth

Vader). In The Power of Myth, a series of viedotaped interviews

with American journalist Bill Moyers, Campbell expounded in the fluent

and eloquent style for which he was known and loved.

Myths to Live By is not the most substantial,

nor the most scholarly of Campbell’s work, but

it is the most relevant to today’s world. It comprises

twelve lectures given between 1958 and 1971 at the

Cooper Union Forum in New York City. Ranging through

such issues as "The Impact of Science on Myth," "The

Mythology of Love," and "Schizophrenia — The

Inward Journey," these talks are highly topical

and well-suited for anyone who seeks to understand

the relevance of myth both to interior personal experience

and to collective trends. Every lecture is packed with

insights that touch on the great questions of life.

Quotable passages abound by the dozens. Here is one:

Myths are telling us in picture language

of powers of the psyche to be recognized and integrated in our

lives, powers that have been common to the human spirit forever,

and which represent that wisdom of the species by which man has

weathered the millenniums. (29)

Campbell’s use of the term "wisdom

of the species" resonates closely with the aim of Metahistory:

namely, to develop versions of the human story in which the wisdom

that guides the species can be communicated. This aim is indicated

by the "mission statement" on the home page: Metahistory

proposes "engagement in a different story about how humanity

can fulfill itself." Not all myths reflect the wisdom of

the species, however. Oral and written narratives in which myths

are preserved can become corrupted over time, rather in the the

way data stored on a disk becomes corrupted. These precious stories,

originally imbued with a saving dose of human sapience, have

all too often been co-opted for cultural, religious and political

agendas that reflect the need to control others, and greed, rather

than the more enlightened motives of the species.

In Background to Metahistory, I noted

the tendency to see in figures such as Jesus a mythical persona rather

than an historical person. This tendency can be traced all the way

back to Herodotus, but it became a methodological tool with Charles

Dupuis (around 1800). Along with philology (study of the historical

development of language, reflected in ancient texts), this tendency

largely determined the modern method of comparative mythology that

emerged with Biblical criticism in the mid-19th century.

The method of reducing history to myth has to be handled carefully,

however. In some cases a figure can have both an historical identity and a

mythical profile. This applies to "Jesus of Palestine" (as

I prefer to call that character), for one or more Jesus-like characters

certainly did live in the first century of the Christian Era, although

it is extremely unlikely that any single of them behaved in

the way Jesus does in the Gospels. The Jesus of the Evangelists is

a composite of several historical figures, highly embellished with

mythological elements. The Pauline doctrine that Jesus the man was

the incarnate "Son of God" is borrowed from the lore of dying

and resurrecting gods so richly described by Frazer and others, but

not just borrowed. It is also altered with a strong ideological twist,

or "spin." In this way, a theological proposition (namely,

the promise of unique redemption through Jesus Christ) becomes adapted

to the policies of state-religion; that is, it becomes a tool for political

control and imperialist conquest.

Ideally, one tries to strike a balance between the historical and the

purely imaginative aspects of myth. Campbell was a sanguine person,

sometimes prone to take extreme views. He hated Catholicism, and often

blasted

it full bore. Generally his aim was excellent, but he could also distort

the materials or disorient his readers with the force of his passions.

One instance always stands out to me. In the second lecture, "The

Emergence of Mankind," Campbell says: "Nor does it matter

from the standpoint of a comparative study of symbolic forms whether

Christ or the Buddha ever actually lived and performed the miracles

associated with their teachings." (29) This view is consistent

with his general tendency to downplay the historical aspects of mythic

and symbolic narratives in the effort to decipher their universal import

as psychic patterns.

While it is true that neither Christ nor Buddha need ever to have lived

as historical persons, someone had to live through the experiences

that produced the mythological narratives attached to those figures.

The "Divine Christ" is a mythological identity attached to

one, or more than one, flesh-and-blood Jesus who actually lived in

Palestine during the Jewish uprising against Rome, and the historical

Buddha was an Indian prince of the 5th Century BCE. In his passion

for the power of myth, Campbell may overlook the fact that real

human experience is at the source of all genuine mythology, although

it may not be the experience of the characters alleged to have played

out the mythic stories.

I would caution readers of Campbell to reflect on this nuance. It is

subtle but also immense.

To my knowledge the lectures in Myths to Live By are without

equal as a clear, gripping introduction to the great themes they treat. "The

Mythology of Love" does the work of volumes of other studies. "Mythologies

of War and Peace" carries tremendous insight on religious ideologies

that support and legitimate violence. To read this book by Campbell,

and this alone, is equivalent to taking a year’s college course

in comparative mythology.

Hamlet’s Mill by

Gorgio de Santillanna and Herta von Dechend: 1969

From the lucid and accessible discourse of Joseph Campbell we now turn

to one of the most dense, digressive and downright exasperating books

written in the 20th century. Perhaps the best that one could say about Hamlet’s

Mill is to compare it to a junkyard, a pawnshop, or a museum packed

with incredible treasures in almost total disarray. (The same could

be said of certain of C. G. Jung’s works, such as Mysterium

Conjunctionis, his magnum opus on alchemy. I think that Jung would

not have objected to his work being compared to a huge dung heap in

which jewels were hidden.) The flotsam and jetsam of the Ages floats

through the pages of this massive treatise, coyly subtitled "An

Essay Investigating the Origins of Human Knowledge and its Transmission

through Myth." Some essay!

The subtitle is intentional, of course. It indicates the reticence

of two scholars from MIT to delve into highly esoteric material, the

kind of stuff that is ordinarily off limits to professors and pundits

of the orthodox mind-set. The subject of their inquiry is stellar mythology:

that is, myths from around the world that relate to particular aspects

of celestial mechanics, especially a long-term cycle of polar rotation

called "precession of the equinoxes." This cycle takes around

26,000 years and may be considered to break down into "World Ages" designated

by the animals of the Zodiac: hence, the Aries Age, the Piscean Age,

the Aquarian Age, etc. Amlodhi’s Mill, a mythological image from

Nordic literature, represents the axial astronomical mechanism that

determines this cycle. As the mill turns, the polar axis of the earth

shifts relative to the celestial sphere, and the Ages are ground from

the grist of human experience. This mythic image is probably the source

of the old saying, "The mills of the gods grind slow, but they

grind exceeding fine."

Speculations on cosmic order run rampant in Hamlet’s Mill,

but after all is said and done, the authors present and explore two

leading propositions:

- Universal legends of continents sinking into the ocean refer to constellations

shifted over the horizon of time by precession (a long-term phenomenon,

not by any means easy to conceive or visualize);

- Many myths from around the world use numbers (72, 4320, 108) that

encode the precise timing of astronomical events and cosmic ages related

to celestial mechanics.

The notion that myths encode astronomy is certainly an eye-opener,

but the authors of Hamlet’s Mill are perhaps a little overwhelmed

by their own discovery. In places they tend to imply that all myths

reduce to nothing but coded astronomy. Or, to say the same thing in

another way, they suggest that transmitting astronomical knowledge

was originally the sole and supreme purpose of myth. Having given some

30 years to the study of comparative mythology, with a special focus

on star-related myth, I cannot endorse this view. Elsewhere in this

site (VIEWS: Myth in Metahistory, Part One: The

Panorama of the Past), I have suggested eight possible "plot-factors" that

may be detected in the materia mythica, astronomical events

being but one of them. The cases where myths do preserve ancient knowledge

of astronomy are always striking, because we of the modern mind-set

tend to assume that only in recent times have scientists come to understand

what is happening in the celestial world. Santillana and von Dechend

are highly effective in dispelling this illusion.

Reading Hamlet’s Mill can be as deeply inspiring as a long

vigil under the glittering constellations of the night sky. It can

also be like dunking your head in a bucket of snails stewed in molasses.

The lasting power of this book lies in the repercussions it has generated,

as much as in its actual content. In the 40-odd years since it appeared,

heirs to the chaotic insinuations of Hamlet’s Mill have

been too numerous to name. Thanks to these two daring authors, the

question of the knowledge of precession among the ancients (i.e., before

Hipparchus, the Greek astronomer said to have discovered precession

around 150 BCE) has become the focal issue in a wide range of debates

on the status and purpose of the archaic sciences. Writers like Graham

Hancock (Suggested Reading in Themes: Origins)

rely on Santillana and von Dechend for the background of arguments

on the high sophistication of Egyptian star wisdom. Contemporary reworkings

of their thesis are too numerous too cite, although no one has yet

solved the riddle of the meaning of the Zodiacal Ages.

Turgid and incoherent as it may be in places, Hamlet’s Mill is

a metahistorical thrill ride not to be missed.

When God Was a Woman by

Merlin Stone: 1976

The feminist contribution to Metahistory is so huge and so crucial

to the revisioning of our story, that it is painful to have to select

one work for classic status. However, Merlin Stone’s book is so

outstanding in style and argument, and so seminal to the field it defines,

that it makes the decision tolerable.

Stone was fortunate to be writing at a time of momentous discoveries

that have deeply affected the feminist rewriting of history. The work

of archeologist James Mellaart at Catal Huyuk in Turkey became known

to the world in 1967, and in 1975 he published The Neolithic Era

of the Near East, opening up a whole new perspective on prehistory.

Until Mellaart did his meticulous reconstruction of the Goddess-oriented

societies of Anatolia, our vision of the "origin of civilization" in

the Middle East was dominated by the patriarchal glories of Sumer,

Babylon and Egypt. The assumption that civilization was a man’s

game was shattered by what Mellaart unearthed at Catal Huyuk.

As noted, Frazer wrote about the empowering role of the Goddess in

the institution of sacred kingship, but prior to Mellaart archeologists

were prone to modest and reticent acknowledgements of the role of women

in building civilization. For instance, Jacquetta Hawkes and Leonard

Wooley (Prehistory and the Beginning of Civilization, 1963)

write with evident temerity: "It is generally accepted that owing

to her ancient role as the gatherer of vegetable foods, woman was responsible

for the invention and development of agriculture." (cited in Eisler,

p. 215, n. 24)

Some five years after Mellaart, Marija Gimbutas produced her first

monograph, The Early Civilization of Europe, revealing the high

level of culture achieved by the non-patriarchal, Goddess-based societies

of the Balkans, and in 1982 she broke through with The Gods and

Goddesses of Old Europe (suggested reading: Origins).

Merlin Stone’s work is complementary to the great accomplishment

of Gimbutas, which it preceded. Whereas Gimbutas concentrated on "Old

Europe" (centered on the Balkans, and excluding Southern Italy

and the Aegean), Stone revealed the vast legacy of the Goddess in the

ancient Middle East. She defined the standard for "Goddess reclamation" later

to be popularized in best-selling studies such as Riane Eisler’s The

Chalice and the Blade (review in Essential Reading).

Originally published under the title The Paradise Papers, Stone’s

masterpiece is remarkable for its even tone and rich content. She is

never polemic, yet she is at least as convincing as the most vociferous

of feminist historians. She is careful in her arguments, yet conveys

the sense of excitement, even astonishment, at the discoveries she

shares:

As I read, I recalled that somewhere along

the pathway of my life I have been told — and accepted the

idea — that the sun, great and powerful, was naturally worshipped

as male, while the moon, hazy, delicate symbol of sentiment and

love, had always been revered as female. Much to my surprize

I discovered accounts of Sun Goddesses in the lands of Canaan,

Anatolia, Arabia and Australia, while Sun Goddesses among the

Eskimos, the Japanese and the Khasis of India were accompanied

by subordinate brothers who were symbolized by the moon.

This is page 2, and the revelations unfold

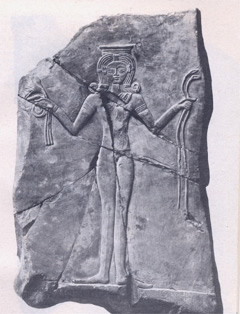

luxuriantly from there. Stone is an art historian and sculptor. When

God Was a Woman contains 20-odd plates of remarkable and

beautiful images of the Goddesss. One of them (plate 8) had an

electrifying effect upon me: Egyptian Goddess Hathor (Canaanite

Ashtoreth), stone plaque, c. 1250 BCE, British Museum.

During my second or third read of When God

Was a Woman I was engaged in writing a book on the Dendera

Zodiac*, the unparalleled masterpiece of ancient sacred astronomy.

This precious artifact is the sole intact working model of

the Zodiac that survives from antiquity. It was discovered

around 1795 in the ceiling of a small chapel in the temple

of Dendera in Upper Egypt (thirty miles north of Luxor), a

site dedicated to the Star Goddess, Hathor, the Egyptian Eve.

Traditionally, Dendera is said to be the birthplace of Isis.

When God Was A Woman is saturated with sexual

lore. Better than any other feminist historian, Stone

shows that the institution of sacred kingship, upon

which all known high civilizations of the past were

founded, could not have existed if the king had not

been empowered by a priestess who represented the Goddess.

In this respect her book provides a resonating coda

to Frazer’s symphonic variations. The original

ritual of empowerment was a hieros gamos, a

sacramental rite of sexual intercourse between king

and priestess. Stone’s elucidation of "sacred

sexuality" stands behind later, more well-known

books such as Sacred Pleasure (1996) by Riane

Eisler, and it resonates beautifully with the luscious

restoration of Sumerian erotic myth by Diane Wolkstein

and Samuel Noah Kramer (Inanna: Queen of Heaven

and Earth, 1984, cited under Sacred

Nature).

Black Athena by Martin

Bernal: 1986

This two-volume masterpiece argues the startling notion that Athena,

who represents Greece, the fountainhead of the Western cultural heritage,

was an Egyptian goddess, a masculinized version of Isis-Hathor, and

she was black. Hence the deep tap-root of White-Western-European-Androcratic-Christian

culture is African. The subtitle of Black Athena is "The

Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization."

Martin Bernal, formerly of King’s College, Cambridge, is a professor

of history at Cornell University. Predictably, his thesis incited enormous

controversy, which continues to this day. Several books devoted exclusively

to the cross-arguments generated around Black Athena have been

published, and Bernal’s ideas continue to be passionately debated.

These volumes (two of a projected four-volume opus) are personal favorites

of mine, rare metahistorical treats.

Bernal writes with ease and openness, so it is never tiring to read

him even though he plows through enormous masses of research. His thrust

is simple and direct: he refutes the "Aryan Model," a script

that explains that Greek civilization originated with Indo-European

(Aryan) invaders who conquered the indigenous peoples of Hellas. Bernal

develops, in contrast, the "Ancient Model" of pre-Hellenic

history, the story told among the ancient Greeks who — let’s

face it — were much closer to their own origins than we are, millennia

later. He shows that everything we conventionally attribute to the

white-male, Aryan, Indo-European complex is a gloss, a "cover

story" that conceals the true derivation of Greek classical culture

from Afroasiatic sources. The title says it all: Athena is black. In

one swift poetic juxtaposition, Bernal achieves a metahistorical shift

of great import. The way we visualize Athena determines the way we

envision the cultural and spiritual heritage of ancient Greece, and

all that later derives from it.

The sweep of Bernal’s vision is suggested by one passage taken

from the Introduction:

This belief [i.e., that Egyptian wisdom

nurtured the Classical world] continued through the Renaissance.

The revival of Greek studies in the 15th Century created a love

of Greek literature and language and an identification with the

Greeks, but no one [of that time] questioned the fact that the

Greeks had been the pupils of the Egyptians, in whom there was

an equal, if not more passionate, interest. The Greeks were admired

for having preserved and transmitted a small part of this ancient

wisdom: to some extent the experimental techniques of Paracelsus

and Newton were developed to retrieve this lost Egyptian tradition

of Hermetic knowledge. A few Hermetic texts had been available

in

Latin translation

throughout the Dark and Middle Ages; many more were found in

1460 and were brought to the court of Cosimo di Medici in Florence,

where they were translated by his leading scholar, Marsilio Ficino.

These and the ideas contained in them became central to the neo-Platonist

movement started by Ficino, which was itself at the heart of

Renaissance Humanism. (Vol.I, p. 24)

In linking the distant Afroasiatic roots of

Greek culture to Renaissance humanism, Bernal touches a theme

revisited time and time again in the metahistory discourse: the

origins and fate of humanism. While it is true, and most important

to remember, that Hermetic wisdom was retrieved and relaunched

in Renaissance Humanism, the reformulation was faulty and humanism

did not serve its stated intention of providing moral and spiritual

criteria for guiding the human species. We live with the failure

of humanism, a failure that metahistory seeks to explain and

correct. Bernal’s study gives enormous depth to this great

and urgent challenge.

Cities of Dreams by

Stan Gooch, 1989

Born in 1932 in London, Stan Gooch studied modern languages and psychology

before devoting himself to independent research on some of the more

baffling questions of human experience, including parapsychology, genetics,

neuroanatomy, and prehistory. Of his fourteen published books, Cities

of Dreams is the ninth in his intensive exploration of a single

theme: what determines human intelligence.

Subtitled "The Rich Legacy of Neanderthal Man Which Shaped Our

Civilization," Cities of Dreams takes an unusual view of

human experience before the end of the last Ice Age. Gooch begins by

proposing that our ancestors in prehistory (roughly, 100,00 - 20,000

BP, Before

Present) may not have been ignorant "cavemen" huddling in

dank caverns. Instead, he builds up the picture of a loose network

of European cave-dwelling peoples who traveled widely, exchanged goods

and communicated with each other, and enoyed a high level of cultural

and spiritual attainment: "Neanderthal civilization." Gooch

carefully explains how the "civilization" of our prehistoric

ancestors ought not to be imagined along the lines of the past high

cultures (Egypt, Sumeria, China, etc). He argues that the Neanderthals

had a culture unique to themselves, and he describes what it was like.

A polymath, versed in disciplines such as archeology, genetics and

parapsychology, Gooch presents a rich and detailed portrait of Neanderthal

life. He emphasizes the subjective dimension of Neanderthal culture,

rather than such external feats as city-building, irrigation and agriculture.

In fact, he suggests that the distinctive mark of Neanderthal mentality

may have been its lack of concern for permanent structures or technological

advantage over nature. The "primitive" mind-set of this lunar-oriented

cave people was deeply esthetic and ritualistic, far more mystical

than practical.

Rather like an isolated dolmen on the horizon, Gooch’s study of

Neanderthal life stands alone and apart from all other speculative

research on prehistory. Due to its radical nature his work has not

been sufficiently assessed and integrated by authors and experts working

in the same field. The three-part essay on prehistory by Ian Baldwin,

featured in the FORUM, is corrective in this respect. It contains many

references to Cities of Dreams, especially in the second installment.

Compared to the other "Classics" cited here, Gooch’s

masterpiece poses unique demands upon metahistorical inquiry. This

is because the material it treats lies at a level of chronological

time that must be accessed by active work of the imagination. And this

process must rely on judgement seasoned by large doses of erudition,

such as Gooch himself exemplifies. Although he cites a vast array of

mythological, folkloric, historical, etymological, anthropological

and archaeological evidence, Gooch cannot develop his hypothesis without

a large degree of invention, or imaginative reconstruction. This is

both the handicap and the hallmark of his book.

Of course, all writers who deal with the distant past must use imagination

to invent it, but according to scholarly protocols, one pretends not

to so do. Among scholars the act of invention is hidden, or denied,

so that it looks as if the prehistorian is simply developing a plausible

scenario from solid evidence. With Gooch, it is impossible to ignore

the act of creative invention, and he does not try to hide it; but

neither does he fantasize and speculate in a reckless, irresponsible

manner. As I reckon it, the failure of his book to meet established

academic standards is due to his not concealing the inventive

nature of his thesis.

The narrational challenge to metahistory exemplified by Gooch is central

to its function: to reformulate the story of our species in poetic-visionary

terms. I alluded to this issue in the essay Tree

and Well, linked to the logo for this site. For the greater part

of the life of the human family, the task of telling the story that

guides the species was encharged to shamans (both men and women) who

preserved it in epic oral tales, long narratives full of poetic language

and visionary content. These tales were, I would argue, vehicles of true

memories of human experience over long periods of time, for myth

in its essential form is a memory of events that once transpired, a

record of actual developments in the cosmos, our earthly habitat, and

in the psychic and somatic life of the species. With Herodotus and

the advent of written history, the "recall" process was radically

altered. As "facts" and a literal, linear style of recounting

them came to the fore, the poetic-visionary memory of the species receded

into the background.

Cities of Dreams is both a model and an inspiration

for the revival of poetic-visionary recall that might

be cultivated in metahistorical discourse from now

on.

Where the Wasteland Ends by

Theodore Roszak: 1989 (written 1971-2).

After a long trek into the distant reaches of prehistory, the last "classic" in

this list returns us to the present and opens a visionary window on

the future.

Theodore Roszak is a cultural historian known among other things for

coining the word "counter-culture." In his book, The Making

of a Counter-Culture, published in 1969, Roszak both critiqued

and championed the quest of American youth to find alternatives to

conventional beliefs and behaviors. Over the last thirty years he has

been relentlessly consistent in his critique of the failings of both

religion and science to provide guidance for humanity. A notable slayer

of sacred cows, Roszak offers positive and inspirational ideas to counterbalance

his intense and unrelenting critique of our cultural and spiritual

norms. His is perhaps the most vibrant and articulate radical voice

in current debate over the fundamental values of Western culture.

The central thrust of Where the Wasteland Ends is clear from

its opening pages. Roszak argues that the failure of religion and the

overvaluation of technology have led us to the brink of self-annihilation.

Because we have not paid attention to what our humanity demands of

us, we have succumbed to a vast range of alienating influences. "Our

culture has struck a Faustian bargain for power over man and nature,

and it will not easily resign its wager. It still looks to its machines,

its science, its big economic systems for security, prosperity, salvation" (xvii).

In exposing the ills of society, Roszak does not leave us without a

remedy. From the first moment of his argument, he proposes that we

can make the necessary course-correction for the species by reclaiming

and re-evolving what we have lost. The "Old Gnosis" is his

term for the magical and sacramental vision of nature that was normative

for the species before we shifted into our current slide, some thousands

of years old, that now threatens to remove us from nature altogether.

All along the way, Roszak does a lot of attacking. The main target

of his lucid rage is "the technological imperative," the

belief-system that insists that all progress due to technology is good

and will benefit humankind. In Roszak’s view the confidence invested

in technological advance is the insanity of Narcissus: we behold an

idealized image of ourselves in the artificial world we are creating,

but the reflection is illusory, and dangerous, because it blinds us

to who we really are.

In the last section of Where the Wasteland Ends, Roszak sets

out his view of "how the Romantic artists rediscovered the meaning

of transcendent symbols and thereby returned western culture to the

Old Gnosis, and what part the rhapsodic intellect must play in our

journey to the visionary commenwealth" (274). Among the Romantics

cited the first and foremost is English poet and artist, William Blake,

who championed imagination as humankind’s divine faculty. The

second culture hero he evokes is Goethe, whom Roszak celebrates for

his little-known scientific work, the best option to the "single

vision" of Newton and Descartes. His chapters on Goethe’s

view of natural morphology, his quest for the "primal phenomenon" in

the plant world, and his colloidal theory of light, are brilliant expositions

that clearly establish Goethe as an outstanding exemplar of the species’ genius.

Over the years I have wondered if I might be the Siamese twin of Theodore

Roszak, separated from him at birth by a meddling pediatrist. We are

both notable for our high regard for the Romantics, although I take

a more cautious view of their great legacy. My strongest personal affinity

with Roszak is perhaps the conviction we share that dissent must

be a potent catalyst to any significant reform in the modern way of

life. The "feel-good factor" is wonderful when it works,

but it can also be a soporific. To those who would object that there

is too strong a dose of negativity in Roszak’s critique, I would

reply that to see deeply into the current malaise and millennial illusion

of humanity is a courageous and empowering act. (In this sense, Roszak’s

work belongs to the "despair work" proposed by Buddhist activist,

Joanna Macy in World As Self, World as Lover.) To engage our

full potential for correction, we need to grasp the fullness of our

deviation from the truth of our species. In the work and play of our

self-redemption,

half-measures will avail nothing.

Those who are unfamiliar with the legacy of Romanticism have a lot

to learn from Where the Wasteland Ends. Roszak’s final

appeal is to the power and beauty of the "mythopoetic" endowment

of the human species. This also is the ultimate calling to which Metahistory

leads, the sacred mission it seeks to inspire.

JLL: Jan 2003

|

|

|