|

|

|

The Gnostic Gallery

A Brief Visual Tour

of Evidence for Gnostics and the Mysteries

One of the difficulties we face in getting a clear sense of

Gnostics, Pagan religion, and the Mysteries, is the lack of tangible

evidence. Most of the original literature of Pagan spirituality

was intentionally destroyed, and the rest was eaten by the ravages

of time. The Greek dramatist Aeschylus wrote over ninety plays,

of which nine have survived intact. This is a good benchmark.

About ten percent or less of all Pagan literature survives, and

probably less than one-tenth of one percent of Gnostic writings

and textual material collected in the libraries attached to the

Mystery Schools. (On the Coptic Gnostic texts found in Egypt

in 1945, see When the Mysteries Died.)

What of other evidence, such as artifacts and architecture?

Consider the Greco-Roman ruins spread

across Europe from the western shores of Ireland and Scotland

down to

the tip of the Iberian peninsula, around the Mediterranean basin

and throughout Egypt and the Levant—all this is evidence

of Pagan religion and the widespread network of the Mysteries.

In

many

cases, the

ruins of classical world are superposed over another layer of

evidence: the megalithic constructions of prehistory. The sacred

grottos of the Black Virgin, for instance, became the sites for

cathedrals and abbeys at Chartres, Glastonbury, and elsewhere.

Shamanic religion in Europa was the prehistorical matrix of the

Mysteries. This archeological evidence is also spread all across

Europe and into the Middle East.

The purpose of this gallery is to display non-textual evidence

presenting

visual

traces

of

the

Mysteries

and the

Gnostic

seers, the telestai, who directed them. In some cases,

the evidence points in a general way to Pagan religion, in

other instances, it indicates specific aspects of Gnostic practice

and Mystery ritual. The value of this evidence lies in its

visual impact (short of going to the places depicted), but

I have supplied brief comments to describe.

ONE: From Prehistory to Delphi

The religion of nature, reflecting the Pagan

sense of life, began with intense immersion in nature. In the

wake of the last deglaciation, circa 10,000 BCE, technology

was

dedicated

to

ritual

arrangement of

sacred

sites. Pombos Dolmen, Portugal. (Julien Cope, The Megalithic

European, p. 424.)

All over Europe, megalithic sites were carefully

aligned to the cardinal points, sunrise and sunset, moonrise

and moonset, and the wheeling of the stars. Some sites, such

as Callanish on the Isle of Lewis in the Hebrides, display an

astronomical sophistication that is astonishing. (Photograph

by Rod Bull in Time Stands Still.)

The "White Lady" of Tassili n'Ajjer in the

mountains of Algeria commemorates a female shaman dancer,

typical of the late Paleolithic cultures that preceded the

age of the

sacred megaliths. Gnosticism derives from archaic practices

of shamanism in which women played an equal, if not dominant

role. (Rock carving in yellow ochre with white spots in red

lines.)

Intimate contact with the "animal powers"

was typical of archaic shamanism. Curiously, ancient seers

found

these powers in the distant skies as well as in the animal

kingdom, not to mention the psychic world. Subterranean caves

were repositories of animal power, the treasuries of the

Goddess. Megalithic sites were devices for monitoring the

animating

powers of the

cosmos. In its late, classical forms, Gnosticism preserved

a highly sophisticated knowledge of astronomy, and relegated

animal powers to an infra-psychic status.

In England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales, many

sites are located in remote places of extraordinary beauty.

The astronomical alignment

of the megalithic circles such as Moel Ty Uchaf in North Wales

incorporates the geometry of pentagon and heptagon.

The interaction between the site and its setting (earth

and sky)

generates an undeniable esthetic effect and may spontaneously

produce altered states of consciousness. (Photograph

by Rod Bull in Time

Stands Still.)

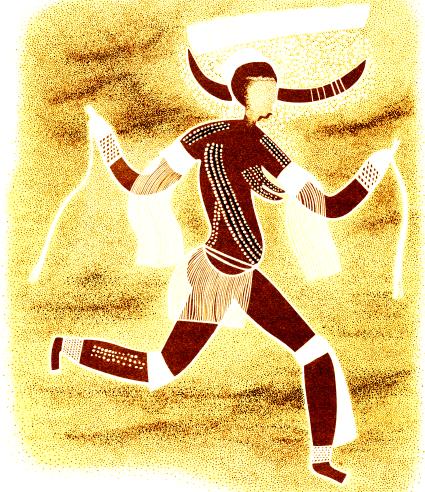

Male shaman in out-of-the-body trance, or

astral projection. His sleeping form is shown on the right.

Eliade emphasized the "archaic techniques of ecstasy," including

trance journeys, in Siberian shamanism, but the practice was

universal. Gnostics refined the techniques of astral projection,

remote viewing, and lucid dreaming —such techniques being

the source of much of the cosmological knowledge, including

their detection of alien intrusion. Shamans in North Africa

previous to 6000 BCE would have participated in

the

Sarahasian

culture

that

spread

across

North Africa and through the Nead East into Iran, before the

great drought and desertification. (Roundhead rock painting

from Aouanrhet, Algeria. In Settegast, Plato

Prehistorian, fig. 59)

Fantastically constructed underground chambers

such as Hal Saflieni (circa 4000 BCE) on the island of Malta

were used for initiatory

rites of which scholars and archeologists, who consider them

to be burial chambers, have no firsthand experience. The shift

from shamanic exploits in the hunter/gatherer setting of open

nature to subterranean rites indicates (in one aspect) the

interiorization of the human psyche, a trend leading eventually

to urban organization

and human-made cultures totally enclosed upon themselves. (Julian

Cope, The

Megalithic European,

p. 318)

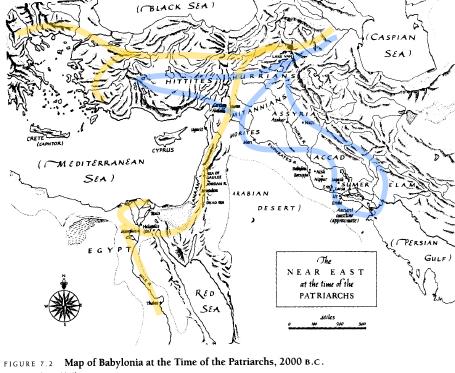

The rise of urban civilization in the Fertile

Crescent depended on the theocratic system of empowerment,

which became male-dominated over time, especially after 1800

BCE. The Zoroastrian priesthood of the Magi, source of the

Gnostic movement, originated around 6000 BCE in northwestern

Iran, in the plateau between Lake Urmia and the Caspian Sea

(main archeological sites, Yanik Tepe and Hajii Firuz). Map

from Mary Settegast, Plato Prehistorian.

There was a split in the Magian Order over

the issue of whether initiates should be involved in statecraft

and theocratic politics. From Lake Urmia, the politically oriented

Magi moved down into Mesopotamia and set up urban theocracies,

but the non-political initiates (later called Gnostics) moved

westward, toward Catal Huyuk in Turkey, and into the Levant

and Egypt where they established the network of Mystery Schools.

Many megalithic circles

were constructed in the open for celebration of public and

popular rites, contrasted to the more secret initiations performed

in

dolmens

and underground chambers. Chromeleque dos Almendres, Portugal.

Julian Cope, The Megalithic European, p. 397).

Map showing dissemination of the Gnostic movement

(gold) from the Urmian plateau into Anatolia and Greece, and

southward into the Levant, Palestine, and Egypt, contrasted

to the Magi who

chose

to

set up and

direct theocracies in the urban cultures of the Fertile Crescent

(blue).

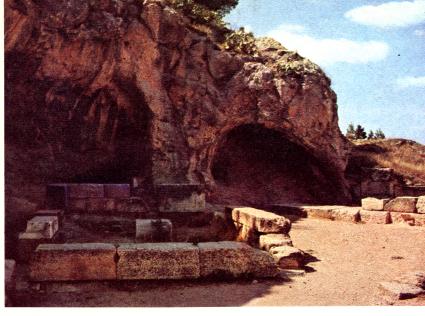

As megalithic sites slowly morphed into temple

precincts, the "underworld" (where non-public initiatory

rites were performed) remained in close and intimate relation

whip with more formal

structures. The Cave of Hades at Eleusis. (In Temples and

Sanctuaries of Ancient Greece, p. 78)

In all indigenous cultures, sacred sites in

nature, and, later, temple sites, were dedicated to the Great

Goddess who represented

the divinity of the Earth. As an image of the fecundity

of nature, she was a "fertility goddess," the residing

spirit of the land, giver of grain, mistress of animals. In

the cultural

perspective, she was the matrix of erotic powers as well as

the superhuman force that drove men into conflict when her

laws were disrupted. Ugarit Goddess with goats and grain.

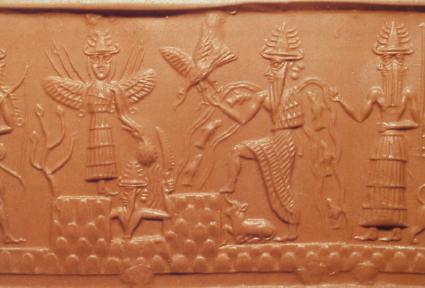

The Sumerian God Enki represents the model

of the ancient theocrat or male chieftain in the first urban

societies.

He was responsible for irrigation of the land, sailing, medicine

(with his half-sister Ninhursag), and other "arts of civilization."

Such theocrats were originally empowered by the goddess cults,

but eventually broke away to form a male-only system of social

and spiritual

authority. Cylinder seal of Enki and attendants.

From 6000 BCE artifacts from

the Halafian culture in northwestern Iran, the geographical

matrix of Gnosticism, were distributed as far as Anatolia,

Syria,

and Greece. Deep in prehistorical times, the organization of

the Mystery cells was determined on an 8-16 pattern, clearly

preserved at Eleusis and elsewhere. This Halafian dish may

have been purely utilitarian, a household commodity, yet it

preserves

the archetypal pattern associated with entheogenic ritual—proving,

perhaps, that the mundane ceremony of eating was based on sacred

norms. (Mary Settegast, Plato Prehistorian, Plate

121a)

A thick flat Celtic stone dish (the "Belenus

Bowl") resembles

the MesoAmerican metote for grinding corn and

mixing sacred herbs. A prototype

of the Grail, it displays letters around the rim. Ceremonial

bowls are among the earliest evidence we have of entheogenic

rites in Pagan Europa. but the ritual significance of these

artifacts is not evident until a later period when participation

in the

Mysteries required special utensils.

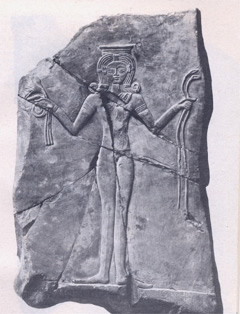

The

Goddess Hathor, the Egyptian Eve, was often pictured with an "omega"-style

hairdo, representing the internal structure of the female organs

of reproduction (fallopian tubes). Here she is pictured with two

snakes in her left hand and sacred herbs in her right. Hathor is

one of many goddesses associated with childbirth, healing, the

preparation of sacred planets, and the serpent power (Kundalini).

In prehistoric times before temples were build, naked priestesses

of her cult would have prepared entheogenic potions for initiation. The

Goddess Hathor, the Egyptian Eve, was often pictured with an "omega"-style

hairdo, representing the internal structure of the female organs

of reproduction (fallopian tubes). Here she is pictured with two

snakes in her left hand and sacred herbs in her right. Hathor is

one of many goddesses associated with childbirth, healing, the

preparation of sacred planets, and the serpent power (Kundalini).

In prehistoric times before temples were build, naked priestesses

of her cult would have prepared entheogenic potions for initiation.

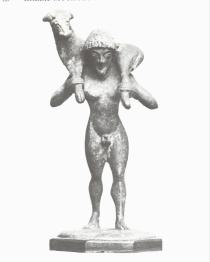

In

the division of labor in prehistory, men undertook animal

husbandry and pasturing. (The practice of breeding animals to

produce finer or stronger types led to the notion

of human eugenics, rigorously applied in selective

breeding of the pharoanic family-lines.) When blood-line manipulation

merged with theocracy, it affected a

deep split between the genders, with all-male domination becoming

the norm in urban societies. But in Pagan religion throughout

the Near East, the good shepherd Dumuzi was always viewed as

subordinate to his consort, the Goddess.

Hermes kriophorus

(c. 1800 BC) is an archaic Greek demigod who became identified

with the good shepherd in Pagan culture. Later, this figure

was coopted

by

Christianity

and attached to the savior. Eventually, it morphs into the figure

of Saint Christopher with a child ("the Christ child") on his

shoulders.

Anatolian house shrine, reflecting gender

balance. Catal Huyuk and other Goddess-oriented cultures

in the Near

East, may fit the "gylanic" model of Riane Eisler. If so, the

balance of genders in these ancient, pre-urban societies may

have been a reflection of the egalitarian structure of the

Mysteries.

Mary Settegast says that late Paleolithic

migrations in the Near East brought the Magi movement deep

into Anatolia

where it merged with native ecstatic rites to produce Orphism:

The religion of the Magi and that later to be known as

Orphism became so similar that modern scholars would consider

using

the one system to interpret the other" (Plato Prehistorian,

p. 251) The Orphic Mysteries were hugely observed down into

modern times. Orpheus playing his lyre to tame the animals

is an archaic representation of the Mesotes. (Domatilla Catacomb,

Rome, 3C CE)

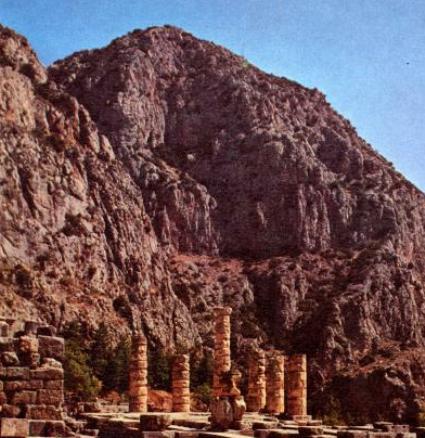

The Temple of Apollo at Delphi with the steep

rock face of the Phaedriades behind it. Delphi's prime was

between the 8th and 5th centuries BCE. It represents a classical

Mystery cult center where indigenous shamanism was brought

to a fine art.

Gnostic Gallery 2: The Splendor of the Mysteries

May 2006. Galleries TWO and THREE in development.

jll

|

|

|