|

|

|

The Gnostic Avenger

Jesus and Magdalene

in the Pagan World

The unique importance of Mary Magdalene for non-Christian Gnostics

arose from her identification with the fallen Sophia, the holy

harlot, the Whore of Wisdom. “The disciple whom Jesus loved” was

probably not John the Divine, author of the Gospel of John and

the Revelation, but a woman variously called Mary, Myriam,

Mariamme. She is not the incarnation of the Aeon Sophia, but

she is a good-enough human reflection of the divinity. In Gnostic

terms, she exemplifies an accomplished Mystery School teacher,

an initiate who knew the secrets of cosmos and psyche as deeply

as any man.

Magdalene’s male counterpart, Jesus, is not the human

incarnation of the Aeon Christos, either. In Gnostic theology,

there is no such incarnation. Jesus was, like Magdalene, a phoster or

enlightened one, fully mortal and fully human. Together, these

two people would have made an unmarried pair

without children, for the Gnostic guardians of the Mysteries— who

called themselves telestai, "those who are aimed" — rejected

procreation as enslavement to social obligations based on blind

biological drives. They would have viewed the shared consecration of

their work in the Mysteries higher than the mundane institution

of marriage. At least that is how this pair might be imagined

if one were to reconstruct a scenario based on non-Christian

elements in the Nag Hammadi materials.

Genuine images of Gnostics and teachers from

the Mysteries are non-existent, mainly due to the fact

that initiates

were vowed to anonymity. It was against their code of selfless

consecration to allow themselves to be depicted in any way

that would foster a cult of personality. Nevertheless, antique

traditions

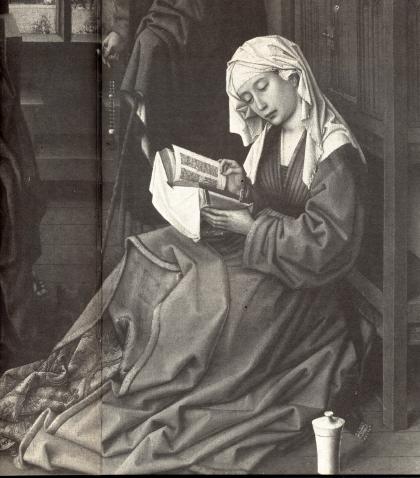

preserve some recognition of the initiatic figure. Mary Magdalene

is often pictured reading a book to indicate that the Gnostics

were intellectuals and teachers who taught literacy and maintained

the high culture of the

pre-Christian world. (The Magdalen Reading by Roger van der

Weyden, c. 1435. National Gallery, London, Plate 18 in Venus

in Sackcloth by Marjorie M. Malvern.)

Christos and the Christ

As I have insisted elsewhere on this site, the difference between

the Christos of the Pagan Mysteries and “the Christ” requires

careful elucidation, especially as it bears on the figure of

Jesus' counterpart, Mary Magdalene. The Christ is an ideological

icon invented by Saint Paul on the basis of the Zaddikite messiah

of the Dead Sea. As such, the term denotes a superhuman being

who, assuming the form of the mortal man Jesus, models the highest

ideal of humanity. The hybrid Jesus/Christ is the central figure

in the Roman cult of salvationism. Hence, the Christ represents

the paradigm of salvation in human guise, but with a distinct superhuman

element implied. (Few Christians understand that the superhuman

element, the power behind Christ, is Melchizedek, the eerie,

clone-like overseer of the Zaddikim; but this is exactly as Paul

claims in Hebrews 6:20.) He is the focus of the Palestinian redeemer

complex discussed at length in my book, Not in His Image.

In the glossary I offer these contrasting definitions:

Christ: (from christos, “anointed

one,” Greek translation of the Hebrew mashiash, “messiah”)

In Christian theology, the “only-begotten Son of God” who

assumes human form to enter history and redeem humanity from

sin. Central figure in the redeemer complex. Said to have been

incarnated uniquely in the historical person called Jesus of

Nazareth; hence, the human/divine hybrid, Jesus/Christ. Regarded

by the faithful as the ultimate model of humanity, and the locus

of human dignity. The divine scapegoat.

Christos: (Greek, “anointed one”)

In Mystery idiom, a divinity in the galactic matrix (Pleroma)

who unites with Sophia to configure the singularity of human

potential, and later intercedes to assist Sophia in the organization

of animal life in the biosphere (the Christic intercession).

Does not incarnate in human form, but may assume a humanoid guise

in the Mesotes.

These definitions indicate not merely a niggling contrast of

terms, but a profound clash of paradigms. The Gnostic Christos

is neither a divine savior nor, in his human guise, the supreme

model of humanity. In the humanoid form of the Mesotes, this

entity is a kind of inner guide, or inner spiritual compass.

Paul preached that "the Christ in us" is a super-human

presence that carries our sense of humanity, but Gnostics taught

that our sense of humanity must be acquired by intellectual

and empathic recognition of the Anthropos, the human species.

In Not in His Image, I call this recognition the species-self

connection (Ch. 23). The difference between the Gnostic Christos

and the Christ signals a vast divergence of views concerning

how we sense “a spiritual presence” in our personal

lives, and how we identify that presence with our innate sense

of humanity.

Pagan Tolerance

In Gnostic terms, the figure of Magdalene is indispensable to

the inner sensing of our humanity. She is a haunting, elusive

presence in the conventional Gospels, but in Gnostic writings

she unambiguously attains her true stature. Magdalene figures

in dialogues in half a dozen NHC treatises; she literally stars

in the non-NHL Pistis Sophia; the Gospel of Mary is attributed

to her. The latter is fragmentary material, with only eight of

eighteen pages remaining. It is found in the Berlin Codex (BG

8502), hence it stands outside the NHC, but it is included in

the canon and carried as the last text in the Nag Hammadi Library

in English.

Much has been made of the Gospel of Mary, but little of what’s

currently written gets to the Gnostic core of her character.

Regrettably, the words attributed to Magdalene in the Gospel

of Mary provide yet another occasion for Gnostic scholars

to indemnify Christianity and discount original Gnostic teachings.

In her book The Gospel of Mary of Magdala, subtitled “Jesus

and the First Woman Apostle,” Gnostic scholar Karen King

argues that “the norm of Christianity was theological diversity” This

statement is intended as praise for the early Christian community,

meant to reflect positively upon Christians today. In King's

view, modern believers can think well of themselves knowing that

their belief-system arose from a rich diversity of views rather

than as a totalitarian dogma. Her viewpoint encourages modern

Christians to be open-minded and tolerant of different interpretations

of the Faith.

But the historical evidence King uses to support this point

shows that well into the 4th century Christianity was so poorly

defined, and so loosely understood even by those who embraced

it, that it is patently misleading to call it by that name.

Devotees were not even agreed on whether to call their savior

figure Christos or Chrestos. King is explicit: “As we have

repeatedly emphasized, at the time the Gospel of Mary was

written, Christianity had no common creed, canon, or leadership

structure.” Precisely so: there was no dogmatic Christianity

in the diversity of the early sects, but Christianity as such

is only meaningful in terms of the dogmas that define it.

King implies that the formative diversity of the Faith, including

Gnostic versions of the salvationist agenda, is a credit to the

open and compassionate spirit of the first Christians, or proto-Christians.

This is a clever spin, and utterly misleading. Professor King

denies that the pluralism she finds so praiseworthy in the first

centuries of the Common Era was entirely due to Pagan tolerance,

soon to be eliminated when the self-styled Christians finally did define

their canon, creed, and leadership!

“The complexity and abundance of early Christian thought” (King

again) was indeed impressive, but hold on a minute. If Jesus

and Magdalene are to be imagined as two prominent teachers in

that time and setting, it cannot have been the Christian

message they were expounding, but Pagan theology of the

kind in which Hypatia excelled.

We are left to wonder, How might Jesus and Magdalene have appeared,

and what might they have taught, had they been initiates from

the Mysteries?

Da Vinci also followed the tradition that

recognized the

high literacy of Gnostics and Mystery initiates. In his Annunciation he

pictured the Virgin poised elegantly at a table, reading

a book. What might be taken for an urn can be seen on the

table to her left. Whatever one makes of Da Vinci's connection

to the Priory of Sion, as an artist he clearly observed the

secret tradition that portrayed Madgalene as literate and red-headed.

For all the attention given to Magdalene's possible presence in The

Last Supper, it is equally, if not more shocking, that Da Vinci

could have subversively portrayed her in the Annunciation. As

the

wife

of a humble carpenter, it is unlikely that the mother of Jesus would

have

been either

literate

or elegant.

Simon and Helen

Gnostic teachings fostered the ultimate, long-range view of

human potential. The goal of initiation in the Mysteries was

not "human divinity" but the highest level of authenticity

and novelty in religious experience, without authority, intermediaries,

or fixed doctrines. Gnosis is a path of illuminism in which we

acquire by our own powers the knowledge that recharges the life-force

and reaffirms our connection to the life-source, Gaia-Sophia,

but Salvationism is a “cross theology” (Karen King)

that bonds us to the suffering of the Divine Victim. Rather arrestingly,

King says “one issue at stake in cross theology was authority.” I

reckon that a Gnostic would find that statement, at least, to

be clear and without error. Gnostic spirituality was vividly

and rigorously anti-authoritarian.

To represent Magdalene as the “first woman apostle” freeze-frames

her in the old paradigm of patriarchal authority and makes her

subservient to the primary male agent of the Roman salvationist

creed (divine or not, depending on your doctrinal criteria).

This portrayal of Mary Magdalene is utterly wrong in Gnostic

terms and does not even follow the prevailing grain of historical

and textual evidence. She was the ultimate outsider in the evangelical

scenario of Jesus as conventionally told.

Jesus and Magdalene pictured in the time and setting of proto-Christianity

cannot be made into evangelists. Given the intense spiritual

ferment of the Piscean Age, and the unprecedented situation that

compelled some Pagan initiates to come out in the open, they

can at best be imagined as a pair of Gnostic teacher-healers.

As such, they would have been agents and exemplars of Chrestos,

the Benefactor awaited by so many at the dawn of the Piscean

Age, and in that role they would have taken a stand against the

authoritarian paternalism of “cross theology.” G.

R. S. Mead advises:

In studying the lives and teachings of these Gnostics, we should

always bear in mind that our only sources of information have

hitherto been the caricatures of the heresiologists, and remember

that only the points which seemed fantastic to the refutators

were selected, and then exaggerated by every art of hostile

criticism; the ethical and general teachings which provided

no such points, were almost invariably passed over. It is,

therefore, impossible to obtain anything but a most distorted

portrait of men whose greatest sin was that they were centuries

before their time.

In addition to projecting Magdalene into the collective imagination,

the recent controversy around The Da Vinci Code has

changed the way we picture her companion. Once Magdalene appears

on the scene, we can never imagine Jesus in quite the same way

again. How then do we re-imagine the Savior? Well, considered

as a Gnostic revealer (phoster), Jesus can no longer

be regarded as the Son of God, a divine being. Nor can he be

identified with the Jewish rebel and messianic pretender of Eisenman’s

sensational profile, based on the Dead Sea Scrolls. Jesus the

Gnostic would have been totally human and non-political. Putting

this figure beside Magdalene, we can picture a couple of Mystery

School initiates who ventured into the public eye, challenged

by the issues of the Piscean Age — especially the main

issue, the quest for personal guidance, consistent with the massive

shift toward narcissism and self-concern at the dawn of that

Age (c. 120 BCE). Because the guidance sought by so many people

at that time was personal, it could not be found within the program

of the Mysteries where ego-death and transpersonal service to

humanity were the criteria.

In fact, such a couple did appear in that very time and setting:

Simon Magus and Helen, the fallen women who was said to incarnate Ennoia,

the “divine intention” of the Pleroma. Simon the

Magian, who lived in Samaria around 50 CE, is often called the

first Gnostic. (The title Magian alludes to the ancient order

of Zoroastrian priest-shamans, the prehistoric taproot of the

Gnostic movement. See the companion article, Gnostics

or Illuminati?) Simon was the first Mystery School initiate

known by name to have appeared in Palestine and argued in public

against the redeemer complex. Christianity did not exist in 50

CE. The figure and mission of the Christian redeemer was not

clear at that time. As Karen King notes, even three hundred years

later there was no agreement on creed, doctrine, or practice.

Simon would have argued against certain theological points in

the Palestinian redeemer complex of the Jewish radicals, the

Zaddikim. Some centuries later these points would have been consolidated

into the rigid dogmas of Roman Christianity.

Hellenistic fabulae (popular tales) recounted in the Clementine

Recognitions (4th C. CE) represent Simon as an evil magician

who debates theology with the apostle Paul and even engages

him in a sorcerer’s battle in the air over Rome. You

do not have to dig out the Recognitions to know who won.

Behind the naive scripting of the Recognitions and

those Hellenistic romances known as the Gospels, a battle for

humanity was taking place. Although the Salvationist creed was

not formalized until centuries later, the redeemer complex with

its program of divine reward and retribution had been developing

since the Babylonian Captivity in 586 BCE. The terrorist theology

of Jewish apocalypticism came to a fever pitch in the Zaddikim,

the extremist cult of the Dead Sea. From the days of the Macabbean

revolt in 168 BC, the dawn of the Piscean Age, Palestine was

rife with messianic obsessions and rocked by social upheaval

due to ferocious resistance to Roman occupation by the Zealots.The

Dead Sea Scrolls present firsthand evidence of this volatile

situation, but they are never cited by scholars like Karen King

who wear specialist blinders. Yet the Scrolls represent the single

most revealing evidence we have of the real setting of the historical

Jesus and his infamous companion, Magdalene.

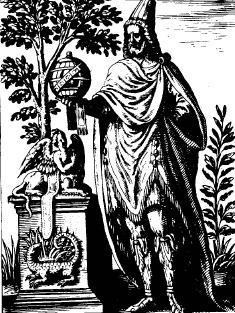

Lacking

realistic portraits of Pagan initiates and Gnostics from

the Mysteries, artists and writers of later generations tended

to depict them as fabulous figures in long robes, surrounded

by magical and symbolic

items. This manner of representation distanced them from humanity

and shrouded them in an aura of mystification. A number of adepts

were pictured in this way, but there is (as far as I know) no

surviving image of a Gnostic couple such as Jesus and Magdalene

or Simon and Helen. (Apollonius

of Tyana,

by Jean Jacques Boissard, c. 1615) Lacking

realistic portraits of Pagan initiates and Gnostics from

the Mysteries, artists and writers of later generations tended

to depict them as fabulous figures in long robes, surrounded

by magical and symbolic

items. This manner of representation distanced them from humanity

and shrouded them in an aura of mystification. A number of adepts

were pictured in this way, but there is (as far as I know) no

surviving image of a Gnostic couple such as Jesus and Magdalene

or Simon and Helen. (Apollonius

of Tyana,

by Jean Jacques Boissard, c. 1615)

By the time of Simon Magus, Palestine had become a significant

threat to the destabilization of the Roman Empire. The entire

region was racked with social and religious unrest, sectarian

violence, and millenarian madness. Into this dangerous atmosphere

stepped a pair of initiates, Simon and Helen — or Jesus

and Magdalene, if you prefer. The substitution is fair, because

the two couples are virtually identical. Either of them could

have been Jewish, for they were a good many Jews in the Mysteries,

which were multi-ethnic in membership. Like Helen, Magdalene

was said to be a prostitute. (In the companion essay, She

Who Anoints, which present a full-length review of King's

book, I consider this controversial factor in Magdalene's profile

in terms of her role as a sacred consort in Pagan rites of anointing.)

The aim of the initiates in those troubled times would have been

to render compassionate service to the many people struggling

through a momentously difficult moment in human history. They

would not have paraded as gods, as they are accused of doing

in “the caricatures of the heresiologists.”

A humanistic portrait of Pythagoras, Greek

initiate

and Mystery adept.

From The History

of Philosophy by Thomas

Stanley (17th Cent).

Teaching Humanity

In that tumultuous time and setting, Jesus and Magdalene could

quite possibly have been an initiated couple from the Mysteries,

like Simon and Helen. The would even have been a Jewish couple

who stood against the hateful fanaticism arising among their

own people. It is essential to remember that the Zaddikite ideology,

the foundation of Christian theology, was not the belief of mainstream

Jews in antiquity, and was, in fact, a source of enormous grief

and anguish among them. (The same situation persists today: Many

sincere believers within the international Jewish community do

not accept that Zionism represents the heartfelt convictions

of Jews, nor that it truthfully serves the aims of their spiritual

tradition.) As a Jewish couple, Jesus and Magdalene would have

felt compelled to face the crisis within their own racial-cultural

tradition, a crisis that shattered Hebrew tradition and caused

the expulsion of all Jews from Jerusalem in 70 CE. As an initiated

couple from the Mysteries, they would have acted differently,

however. Their work in public life would have been dedicated

more to the problems of personal guidance raised by the new Zeitgeist

of the Age, and less to specific issues concerning the fate of

the Jews.

So imagined, this couple cannot have been Christian in any conventional

sense of the term. Neither would they have been a married Jewish

couple bent on having children at a biological extension of their

faith. See my article in The

Secrets of Mary Magdalene,

edited by Dan Burstein and Arne de Keijzer.) The power of Magdalene

is just this: when she enters the picture, Jesus sheds the aura

of divine redeemer. This couple do not represent the familiar

savior and the “first woman apostle,” no matter what

kind of retrofit is put on them. Professor King claims that

Mary of Magdala, in her “legitimate exercise of authority

in instructing the other disciples,” preached the unique

message of Christianity to the world: “Christian community

constituted a new humanity, in the image of the true Human within.” The

notion that the first Christians discovered a new sense of humanity

unknown to anyone before them is typical of the arrogance of

Salvationist creed. The claim that Christians, then or now, represent

the human species in some unique manner, better and more deeply

than other people, is holier-than-thou and nonsense.

“The image of the true Human within” is not, and has never

been, copyrighted to Christianity. I would argue that the term “true Human” (Coptic

PITELEIOS RHOME) in King’s translation of the Gospel of Mary is

an expression of the Anthropos doctrine of the Gnostics, the Mystery

teaching on the pre-terrestrial origin of humanity, not the divine redeemer.

Scholars

who

use Gnostic material to revisit and revalorize Christian doctrines rarely

acknowledge

the

originality of their sources. Marvin Meyer fares a little better than

King in attempting to put Gnostic writings “into language that

is meant to be inclusive… [using] non-sexist terms and phrases.” Meyer

uses “Child of Humanity” rather than the familiar “Son

of Man.” The consequent shift of language can be startling. For

instance, The Secret Book of James says, “Blessed are

those who have spread abroad the good news of the Son before he descended

to Earth.” Meyer renders it: “Blessed three times over are

those who were proclaimed by the Child before they came into being.” This

language comes close to denoting the Anthropos, the numinous genetic

template of the human species projected from the galactic core of the

Pleroma, thus giving some idea of what Magdalene would really have been

teaching. (Meyer also incorporates Mystery jargon, “three times

over,” referring

to the status of hierophant, e.g., Hermes Trismegistos; hence he implies

that the identity of the Child or authentic humanity is a matter of

initiated knowledge.)

But Meyer almost loses the genuine non-Christian message

he wants to capture. “The

Son before he descended to Earth” is the Anthropos projected

from the Pleroma before the Earth emerged, understood in Gnostic

terms, but sounds dangerously like the Incarnation in Christian

terms. The

substitution

of Child for Son humanizes the language of

the

text but verges away from

the

Mystery teaching on the Anthropos. Karen King’s allusion

to “the

image of the Human within” is actually closer to the

Gnostic meaning, although she does not bother to acknowledge

that the Anthropos

doctrine, distinct from the redeemer complex, is the source

of this language.

By retrofitting Magdalene into the redeemer paradigm, the Gnostic

message is co-opted and distorted, time and time again. In

their own day Gnostics saw this happening and protested with

vehemence and eloquence. The distortion continues, effectively

obliterating from Magdalene’s character and teaching

any traces of “the side that lost out,” as King

characterizes them. With Jesus and Magdalene, it is one version

or the other:

either they represent Gnostic illuminism or they represent

the salvationist platform of redeemer beliefs. It cannot be

both.

Any admixture of cross theology immediately destroys the authenticity

of the Gnostic couple and their message to humanity about what

it means to be human.

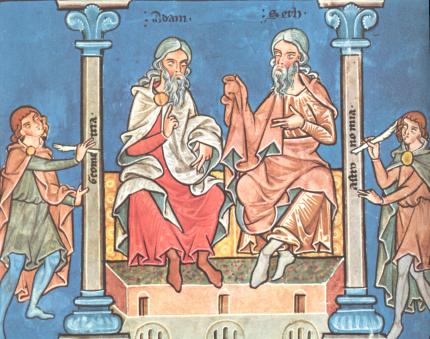

According to their own account of their origins,

Gnostics traced their sacred tradition back to Seth, one of

the sons of Adam. Sethian teachings emphasize the power of

the Divine Sophia and even downplay the Christos in the mythic

scenario of Sophia's fall. One of the essential claims of the

Sethians was to preserve the teaching of True Humanity,

the Anthropos, not to be confounded with the image of perfect

humanity in Jesus Christ. (Adam and Seth, miniature from the

Royal Chronicles of Cologne, 1238 CE. National Library, Brussels.)

She Who Anoints

The first step in a genuine, enduring revival of Gnosis in our

time would be to recognize what is original to Gnostic teachings

in the

Mysteries and refrain from co-optation intended to produce a “new,

improved” version of Christian beliefs. Magdalene could

be the key factor in the revival, but so far she is contributing

to

a lot of distortion. The problem with the pop occultism of Baigent

and others, including Dan Brown, is that it makes Mary Magdalene

accessory to an altered patriarchal scenario rather than to an anti-patriarchal

scenario. The Priory of Sion, the alleged secret society that

is said to have preserved the truth about Magdalene’s role

in Jesus’ life, is the instrument of a monarchist cabal

intent upon restoring the blood-line of Jesus in Europe. True

or not, real or not, this scam is about as patriarchal as you

can get.

Even if the Priory does not exist, the message is clear: Magdalene

is valued for her biological role as a vessel of the “holy

blood” of Jesus, the sangraal. Behind this fantasy

lurks the crypto-fascist mentality that pervades almost all forms

of

modern esotericism. If Jesus was divine, the bloodline originating

from him is unique on earth. If he was a mortal man, the bloodline

still has paramount claim to regal status, for the “King

of Kings” ought rightly to be the progenitor of the kings

who rule the world. In such ways as this are we once again delivered

into the insidious game of the theocrats.

Nevertheless, The Da Vinci Code has deeply

affected many people by the way it reintroduces the Divine Feminine

into religious life. This

angle of the novel comes closer to the Gnostic profile of Mary

Magdalene as a teacher of True Humanity, PITELEIOUS RHOME, and

the intimate companion of Jesus, whom she anoints. At best, it

points

far

beyond the

Gospel setting to the unique power of Magdalene as a numinous

figure in human imagination.

As noted above, Christos, Greek equivalent to the Hebrew

mashiash, means “the anointed.” Originally

this was an honorific title given to sacred kings in Mesopotamia.

It had

no divine

connotation and still does not for devout Jews. As a title of

affiliation rather than divinization, it designates a man who

carries the authority of the Father God. Theocracy

is an all-male domination system, the crux of the patriarchal

agenda. Patriarchy is about men anointing men, or, in bureaucratic

terms, men appointing men. Zoroastrian Magi who anointed ancient

kings in the Near East were in a position of authority and control

over the men they empowered. Clever priests

pandered

to

the egos

of the

theocrats, treating them as if they were divine, descended from

gods. The pretence of divinity fits the crypto-fascist agenda

like it was custom made for it: Constantine recognized this clearly

when he insisted on the divinity of Christ so that he could claim

superhuman authority for the Roman Empire. The fact that he stopped

short of declaring himself divine, as some late Roman emperors

did, is a measure of his political savvy. As a human claiming

divinity, he could be questioned. But by enforcing the divinity of Jesus,

Constantine made sure that no one could question the authority he held

in the name of the Son. And he made the penalty for doing so, death.

In pre-patriarchal

times, anointing was a sexual-hedonic rite, the heiros gamos (sacred

wedding) of the Goddess, who was represented by a priestess,

with the

man who would be king. Like a powerful magnet, the figure of

Magdalene draws our attention to this forgotten rite and the

empowering woman who performed it.

For Gnostics of the Mysteries, the human figure of

Mary Magdalene had a mythic counterpart: the Goddess Sophia,

the consort

of

the

Christos

in the Pleroma. The Gospel

of Philip describes the erotic sacrament

in the nymphion (“bridal chamber”) where

initiates ritually reenacted the divine coupling that produced

the Anthropos, the

luminous template for humanity. Myth is repeated in the sexual

ritual, the two genders are reconciled in the nymphion, and

the celebrants emerge with their sense of humanity renewed and sharpened. The

Gospel of Philip (73.5) affirms, “Those who do not

receive the resurrection while they yet live, when they die will

receive nothing.”

For Gnostics, resurrection was vital-sexual regeneration experienced

here and now in the living flesh. Magdalene is traditionally

pictured with an urn, the vessel of anointing. All the evidence

indicates that this woman would have been seen by her Gnostic

peers as a courtesan charged with ritual anointing and instruction

in the mysteries of the nymphion – a “sacred prostitute,” to

apply the unfortunate term that often turns up in the current

flood of books about her. No one lately seems to have gotten

her tawdry

image as right as Marjorie M. Malvern, whose Venus in Sackcloth was

published in 1975, almost thirty years before the present furor

over Magdalene. Malvern shows that “the connection of the

Magdalen with a goddess of love… is unbroken and unmistakable” in

European art and literature from classical times. “Transcendence

of the fear of death through the celebration of the ‘mystery’ of

sexual love and of life on the earth” is the signature

of the consort, she who now re-ignites the image of the Great

Goddess in the collective imagination.

The Gnostic Avenger

In the perspective of the Pagan Mysteries, Magdalene’s

role in the life of Jesus was to anoint the anointed, but the

mortal

man

was not

made divine

by

this ritual. Rather, it showed that he was acknowledged by a

representative of the Goddess Sophia to be a teacher of “the

Human within.” Consider this notion against the proclamation

of Paul in Hebrews 6:20, that “even Jesus [was] made a

high priest after the order of Melchizedek.” This astounding

disclosure alarmed the Zaddikim, who saw Paul spouting their

secret doctrines to the public. It also would have alerted Gnostic

observers to the ultimate pretensions of the Zaddikite sect on

the Dead Sea, a group whose sexist and genophobic views were

diametrically opposed to the sexual balanced humanitarianism

of Gnosis.

Gnostics like Jesus and Magdalene did not normally do religion

in the public eye. They did not enter politics to change the

world or accomplish social reform, but in their work in the Mysteries

they did everything they could to nurture people who would build

a society that did not need to be reformed, because it was

good enough on the basis of the moral integrity of its members.

As telestai, Jesus and Magdalene would have consecrated their

lives

to harmonize

culture

and nature,

and,

most certainly,

to keep theocratic politics (the only kind that matter on this

planet) at a safe distance from schooling their fellow humans

in co-evolution. Like many other guardians of the Mysteries,

they managed to do all this in the Near East and in Europa for

about six thousand years, the last four thousand after patriarchy

had got a good head of steam rolling.

Such is not the achievement

of individuals head over heels in love with their own divinity.

Allowing for the presence of Mary Magdalene in the story of Jesus

shatters the pretences around deification, and blows patriarchal

presumptions about God out the window. It also weakens, rather

than strengthens, the crypto-fascist agenda attached to the “holy

blood, holy grail” fantasia. Magdalene is the flesh-and-blood

defiance of the patriarchal overthrow that shunted sacred mating

into oblivion, in favor of the all-male messiah club and the

begetting or royal heirs. She is the one who anoints virginally,

without conception.

She is the Gnostic Avenger. * * * * *

Those on the scene in Jerusalem at the time,

around 35 CE, did not know if the women at the gates wept

for Jesus crucified

or for Dumuzi, the Sumerian tender of flocks whose lover was

the sensuous goddess, Inanna. Today, facing the prospect of

a Gnostic revival, we know that Inanna

and

Dumuzi, the goddess and the shepherd king, are mirrored in

Magdalene and Jesus, and their relationship has nothing to

do with self-deification, or concocting a better form of Christianity,

or reinstating the Merovingian dynasty in Europe. This couple

is about Pagan eroticism, the hedonic rites of human passion,

and Gnostic sacramentalism. In their union and in their teaching

alike, they celebrate the divine body of Gaia-Sophia in whom

humankind has its pleasure and its atonement.

(Like many other images thought to be of the

Virgin Mary, "The Madonna of the Sacred Coat" by C. B. Chambers

(ca. 1890), presents a Magdalene-like figure in a gentle, welcoming

attitude, thus allowing a glimpse of how a female Pagan initiate

might actually have looked.)

|

|

|